Word count: 1523

This is a combination of the most thought-provoking discussions I have engaged with in the last few months. They represent my introduction to the field of Digital Humanities and my first thoughts on a number of important issues in our modern digital world.

Writing & the Post-Blog Era

A Discussion on Mark Mario’s article “Teaching Writing in the Post-Blogging Era”

Word Count: 201

What stands out to me is the trends within blogging. As a relatively new phenomenon, we have already witnessed great shifts in this category of writing. Traditional blogs have birthed a multimedia revolution. From textual blogs, microblogging was born. With the addition of audio, video and photography, podcasts and photo and video blogs were born. These categories of blog, while still routed in the traditional, have allowed for an expanded sense of expression – whether that expression is in the creative or academic.

This multimedia development for me is the most exciting. The ability to link to other writings and embed visuals combined with the almost unlimited scope of sharing that the internet provides completely changes how humans can express and connect. For students in the modern day, it certainly seems archaic to write papers in Time New Roman and physically hand them into a gloomy college office at a particular time and date. Research writings and, even more, personal works should be given the room to include the full plethora of media types that we have access to in today’s society. Creating nuanced and interesting works relies on this ability – that is the ability to express ideas through all avenues available.

Mario, M.C. (2019) “Teaching Writing in the Post-Blogging Era,” markcmarino.medium.com., Medium.com, 29 August. Available at: https://markcmarino.medium.com/teaching-writing-in-the-post-blogging-era-ab7848247e33 (Accessed: October 1, 2022).

Individuals & Societies of the Web

A Discussion on Filter Bubbles & the Contract for the Web

Word Count: 646

The early days of the internet were exciting. The ever-expanding connectivity between people and ideas seemed to have no limit. Thousand-page encyclopaedias, reduced to pixels on a screen and the distance to any shop in the world, reduced to the other side of your kitchen. Society could surely only benefit from this revolution in communication and connection.

With the online transition in full swing, the amount of information available online increased exponentially. The companies at the forefront of the web began to see a problem: figuring out what information to show which people. Queue the personalised feed. By analysing what web users had viewed, clicked, liked and shared in the past, these companies could create models that would predict what users would like to see. Content platforms would tailor their homepages to specific users. This expanded into all areas of these sites and even to search results. Eli Pariser (2011) described asking two friends to run a Google search for ‘Egypt’. The first friend received news about recent large-scale protests and the political crisis in the country. The second friend got travel information and encyclopaedia results. These personalised results for the exact same search term may seem quite useful. The logic being that the first friend has probably searched for current affairs many times and the second has searched for travel information. However, when searching for objective facts, this personalisation can have the effect that some people are completely filtered out of certain types of content by “The Filter Bubble”.

“A squirrel dying in front of your house may be more relevant to your interests right now than people dying in Africa.”

Mark Zuckerberg (Kirkpatrick, 2011)

This bubble is the result of our replacing of the human content editors of the past with the digital algorithmic editors of today. Picking up and analysing many points but aiming only to induce more clicks and engagement. Saying nothing of the effect on individuals, it’s clear that this is not what society needs.

The Contract for the Web aims to address these issues. Much like the establishment of journalistic ethics in the twentieth century, this contract aims to establish a set of principles to protect both individuals and society at large from the negative effects of the web. For example, Principle 5 focuses on the privacy of individuals and control of their data. It advocates for clear explanations of privacy processes and easy to use control panels to decide on various data options. It calls on corporations to limit data collection and use best practices in UI design to help users intuitively control their data. Principle 8 on the other hand deals with society. It advocates the webs use for building strong communities centred around civil discourse and human dignity. It is here where the individual and the society potentially clash.

Lack of privacy and uncontrolled data collection has led to the birth of very accurate personalisation algorithms. These algorithms have created filter bubbles, feeding individuals only what they have previously indicated they will engage with. This has walled individuals off from content they have refused to engage with. Now, as data controls and privacy laws begin to be enforced, many people are limiting the amount of personalisation platforms can perform. This in turn opens them up to information they may find disagreeable. And this is where conflict can occur.

Data and privacy are huge issues of great importance. But, without proper education on civil discourse people may be unable to process the newly unwalled lands of the web that we are creating. We have already seen how online battles have been played out in the real world. Disagreements on the keyboard becoming riots on the street – this is clearly already an issue. If we only focus on those issues that pertain to the individual, we risk furthering an issue that can engulf our society as a whole.

Contract for the Web (2022). Available at: https://contractfortheweb.org/ (Accessed: October 15, 2022).

Kirkpatrick, D., 2011. The Facebook effect: The inside story of the company that is connecting the world. Simon and Schuster.

Pariser, E. 2011, Beware online “filter bubbles”, online video, TED.com, viewed 16 October 2022, https://www.ted.com/talks/eli_pariser_beware_online_filter_bubbles.

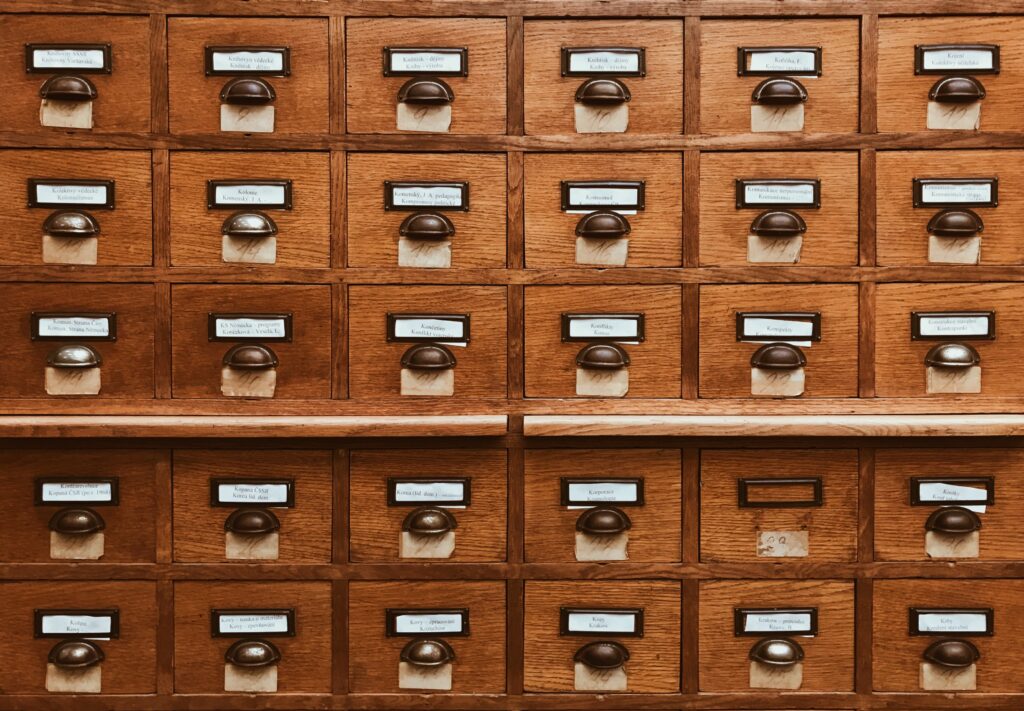

The Abilities of Archives

A Discussion on the Power & Considerations of Archives.

Word Count: 666

Archives are to many seen as boring, archaic filing systems where irrelevant documents are stored when they are no longer of use. Yawns of derision usually meet the over-stylised library basement scenes in documentary films. However, with the digitisation of many of these archives, new tools and techniques are coming to the fore to bring them to life in new ways and extract the often very useful and important accounts they hold.

István Rév (2020), a political scientist and historian and a central figure in the open access movement, believes archives are now essential to understanding the development or history of an individual or a collective past. Their role has developed from the boring to the revealing and, thus, they have become a target for the shedding of light on historical events, people and institutions. For Rév, it is unfortunately not as easy as simply opening up historical archives to the public. The privacy of individuals and corporations must be respected, intellectual property and copyright restrictions must be factored in and constraints such as national security and secrecy provisions may hinder openness. This web of overlapping and often contradicting rights and responsibilities makes the job of opening up access to archival information extremely difficult.

Yet, it is still imperative. Firstly, access to one’s own information is now seen as “a natural part of the widening concept of basic human rights” TK. With the adoption of GDPR regulations and the setting of a best practice for personal data and privacy rights, many of the largest corporations in the world are having to rethink their business models. These business models revolved around data mining and targeted advertising. Tim Worstall (2012) asserted that “if something is free, it must be you that is being sold”. With these concepts becoming widely known in civil society, privacy and personal data rights have strengthened and in many ways this stands in the way of open access to archives of data. Hurdle number one.

The imperative remains. Basic individual data aside, the concept of open access is now understood to be the unimpeded right of access to any documents of political, historical or cultural significance. Those documents that have been produced with direct or indirect public funding or that document important historical events are now seen as a public good. This becomes even more important in the aftermath of a regressive regime or abhorrent human catastrophe. Documentation of reprehensible events cannot only lead to prosecution but can serve as a small glimmer of light to those that lived through it. Again this does not come without its challenges. The protection of third parties that happen to be mentioned in documents becomes of vital importance. Wrongdoing committed on a system level does not necessarily mean wrongdoing at a specific individual level. This need to balance the public with individual rights can slow or even prevent the opening of archives. Hurdle number two.

Where does the imperative lie? More accurately with who does the imperative lie? Rév argues that the institutions that hold the archives have a duty to balance this web of interests. These institutions in many jurisdictions have a legal obligation to protect the identities of individuals and apply copywrite and secrecy laws to the access rules of their archives. However, it is the second imperative – public good – where things are more difficult. Institutions must have it as a founding goal to release the largest amount of data that they can to the public without endangering individuals or intellectual property.

In Ireland, we’ve seen through the scandals around Mother and Baby Homes and other state institutions, the lasting effects secrecy, restriction and active suppression of documents can have on individuals and families for generations. Adopted children being unable to access their own information and birth families the same. As we move forward, these lessons must teach us that balancing rights and responsibilities takes active involvement and thought and baking this process into our archives has the power to protect, reveal and even inspire.

Rev, I. (2020) “Accessing the Past, or Should Archives Provide Open Access?,” J. Gray and Eve, M. P. in Reassembling scholarly communications: Histories, infrastructures, and global politics of open access. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, pp. 229–247.

Worstall, T. (2012) “Facebook Is Free Therefore It Is You Getting Sold,” Forbes, 10 November. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/timworstall/2012/11/10/facebook-is-free-therefore-it-is-you-getting-sold/?sh=71863ca22cfe (Accessed: November 14, 2022).